Der vom Nazi-Besatzer zerstörte Friedhof befindet sich in dem von Staatsforste Oberförsterei Jarocin verwalteten Gebiet, das zusammen mit der Stowarzyszenie Nasza Gmina [ngo] die Erinnerung an diesen Ort wiederherstellt.

Friedhof und Matzevot Juden im Książ Gedächtnis wiederherstellen

Jewish community in Książ

Książ, which was a castellan stronghold before 1273, gained city rights in 1407. Initially, the stronghold belonged to the monastery of St. Vincent on Ołbin in Wrocław, but in the first half of the 13th century it passed into the hands of noble families and remained a private town until the end of the 18th century. Even in 1793, residents paid annual fees and rents to the then owner Wacław Wyskota Zakrzewski.

Poland till the end of 18th century

It is not known exactly when the Jews appeared in Książ. We estimate that it was about the middle of the 16th century, although they began appearing in Poland in the 12th century. At the beginning of the 13th century, they were already in Greater Poland, which is confirmed by numerous information, especially regarding Jews from Kalisz. The type of culture and professional structure favored the formation of their clusters in cities. They created separate enclaves subordinated to their own self-government. They obtained separate privileges, excluding them from the municipal judiciary. Thanks to this, the forms of Jewish settlement shaped in Poland in the 14th-15th century differed from those existing in Western Europe and Mediterranean countries, where ghettos were established. During this period, there were waves of mass influx of Jewish people – from the west, south and east, associated with economic persecution and bloody protests against Jews, e.g. during the plague epidemic. Written sources confirm the existence of around 80-90 Jewish communities in Poland at the end of the 15th century.

From the mid-sixteenth to the mid-seventeenth century there was an increase in the number of Jewish communities and their organizational and cultural development. By the end of the 16th century, there were about 200 Jewish communes throughout Poland, but most of them were in Red Ruthenia.

In 1563, the royal administration of Poland introduced pogłówne – a tax paid by Jews to the treasury, intended for military needs. This tax was then calculated for each person, except for children under one year of age. It amounted to 1 zloty and did not include only the poorest. A census made for tax purposes lists 19 Jews in Książ in 1563. The nearest clusters according to this census are Śrem (110 zloty tax) and Bnin (11 zloty). In the neighborhood, the presence of Jews shows a mention from 1582 about a fire in the synagogue in Żerków.

From the mid-seventeenth to the end of the eighteenth century, there was an outflow of Jews from the Polish lands on the one hand, and rapid demographic development of existing communes on the other. The demographic structure of cities in which Jews gradually constituted an increasing percentage also changed.

Prussian partition

Jews settled in Książ permanently. We know that in 1771 there was a synagogue, or at least a house of prayer. It results from the mention made in Polish from October 30, 1810. The information appears on the seal bearing a communal seal, confirming that Markus Abraham, 39 then, son of Abraham Jacob, born on December 13, 1771, was accepted into the Abrahamic covenant after eight days. The document was signed by the heads of the Jewish community in Książ: Abraham, son of Akiba, and Salomon, son of Jacob. At that time, Jews, like townspeople and peasants, did not have names.

Information on the significant presence of Jews in Książ is contained in the agreement of February 22, 1782 regarding the consent of the city authorities to the synagogue. Another document preserved is a privilege dated January 1, 1788. In this document, the city owner consents to Jews trading tobacco and elbow goods, excluding materials, and slaughtering. In return, they were required to pay an annual tax of 200 florins to the owner of the city. In 1797, 73 Jews lived in Książ, which constituted about 10% of the total population of the city. Among them were four tailors, a baker and a bookbinder.

With the third partition of Poland, Jewish settlement was subordinated to the legislation of the partitioning powers. In 1797, the Prussian king, ruling at that time in Greater Poland, issued a decree concerning "the arrangement of Jews in the provinces of South and East Prussia". This decree subjected Jews to general jurisdiction, deprived the judiciary of Jewish communities, and deprived rabbis of their supervision over schools. At the same time, a policy of assimilating Jews with German society was pursued in the Prussian partition. Despite this, opposite tendencies were noticeable – to assimilation with Polish society. Many Jews fought together with Poles in uprisings against the partitioners.

However, this Prussian state pursued a methodical policy of equalizing the rights of Jews with the rights of Christians, initially only towards German Jews. In 1833, the official ordinance "regarding Jewry in the Grand Duchy of Poznań" divided Jews into "naturalized" and "tolerated". Naturalized Jews received civic rights and a considerable scope of freedoms, provided they demonstrated knowledge of German and an appropriate property census.

In Książ, among 8 Jews, a naturalization patent was granted to Baruch Moses Jaskulski, son of Jacob. He was a deputy rabbi here for 18 years from around 1829, then he moved to Mieszków for three years to settle for the rest of his life in Osieczna around 1850, where he died on December 8, 1852.

In 1840, 219 Jews lived in Książ, which constituted almost 20% of the total population of the city (1,109 people). Around this time, the Jewish community opened an elementary school, which was located in a house next to the synagogue. At the beginning of 1848, out of 103 houses in Ksiaz, 26 belonged to Jews.

In 1848, the rights of all Jews were leveled in Prussia, and the constitution adopted in 1850 formally accepted the abolition of all divisions in society. From that moment, Jews could study, work in a chosen profession, conduct any economic activity.

Prussian partition after 1848

1848 is not an accidental date. Revolutionary movements called the Spring of Nations swept across Europe. Under their pressure, the Prussian king went for far-reaching concessions towards democracy. On this wave, an uprising broke out in the Grand Duchy of Poznań, which led to the most dramatic event in the history of Książ. On April 29, the overwhelming Prussian army invaded the Polish army camp located in Ksiaz and defeated the city's defenders after a four-hour hard battle. The wooden buildings were mostly burned down. Before the battle took place, at the end of March 1848, a local Polish National Committee was established in Książ. Among the 13 members of the Committee were three Jews: Matulke Gotlob – the innkeeper, Fabian Bernstein – a merchant, Jakub Hirsch – a merchant. Two Jews also sat on the revolutionary municipal security committee.

Not all Jews at that time favored Poles in the fight against Prussia. It is said that representatives of the Jewish community together with the Germans from Książ betrayed the defenders of Książ and showed Prussian soldiers the passage through which they invaded the city. On the other hand, the hospital for the wounded improvised in the pharmacy was led by a Jewish doctor – Dr. Zygmunt-Zobolon (Zewulun?) Dembitz (Dębicz). This doctor was taken prisoner together with the insurgents and wounded whom he looked after during transport, ignoring the persecution of Prussian guards. There is also a second Jewish doctor taking care of the wounded in Książ – Dr. Elijah Wachtel.

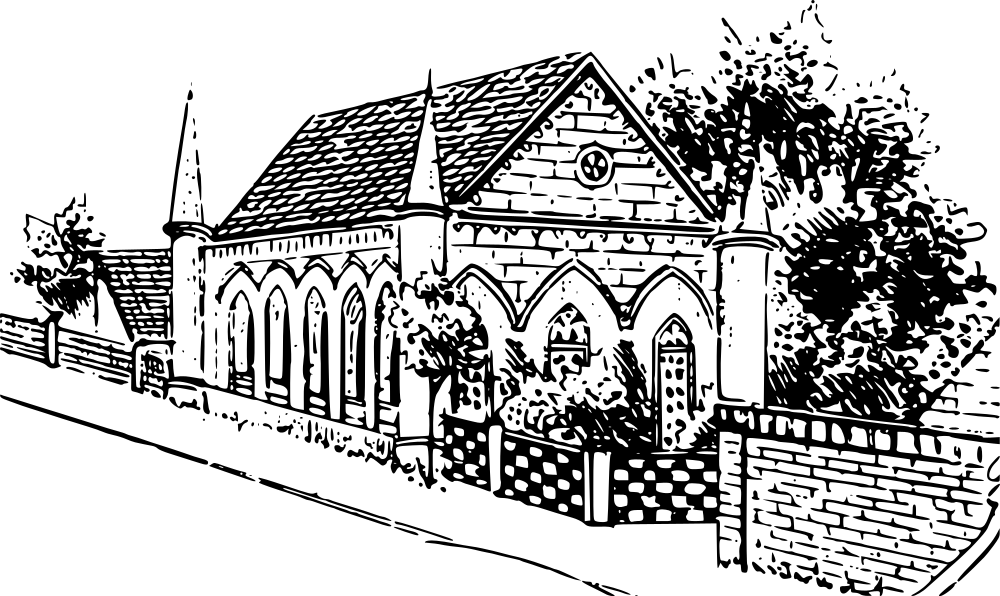

The fact is that, after the events of 1848 and considering the new German law, Jews gradually moved to the German side. However, it seems that peaceful coexistence continued in Ksiaz. Three communities – Polish, German and Jewish – sought help in rebuilding the city on their own. The burnt synagogue and school were replaced by new brick buildings, opened on October 4, 1849. In the years 1867-1868 the Jewish community built a mikvah – a ritual bathhouse, and in 1888 it mourned the cemetery.

In 1872, 34 Jews paid taxes to the city for their profession, in 1886 – 26 Jews, including 4 tailors, 2 furriers, a baker, a butcher and a shoemaker. In the years 1891-1892, 22 Jews paying city tax, and in 1907 – 12. These numbers, as well as the number of the Jewish community in Książ (1849: 200, 1857: 200, 1871: 182, 1880: 153, 1890: 141 – 30 families, 1895: 113, 1898: 118, 1901: 100, 1905: 91, 1907: 52, i 1913: 43) show the gradual outflow of Jews from Książ, most likely in search of better living conditions and greater opportunities in larger cities or in in general in Germany. This is also confirmed by the list of students at the Jewish school. It is known that in 1893 it was attended by 25, and in 1899 – 16 children. The teachers were: H. Thilo (1887), J. Goldberg (1899) and Löb (1905). After 1905 the school was dissolved.

There were two brotherhoods in the Jewish community: Chewra Kadisza and Chewra Ner Tamid. The first, run in 1899 by Jaroczynski and Baruch, was a funeral brotherhood, which dealt with the care and prayer of the sick, prayer and organization of the funeral and organization of prayer on the anniversary of death. The Brotherhood of Ner Tamid, called the brotherhood of eternal fire, guarded the oil for eternal light that always burned in the synagogue. It is known that Ludwik Kwilecki was the chairman of this brotherhood in 1907.

The community was managed in turn by: Mor. Kantorowicz (1887-1911), M. Kunz, Jul. Tuch, S. Baruch, S. Jaroczynski, and J. Kallmann. Jews also had their share in managing the city. In 1905 and 1911 (according to various sources), the councilors were Kantorowicz and Tuch.

Second Republic of Poland

The victory of the Greater Poland Uprising of 1918-1919 and the incorporation of Greater Poland to the reborn Republic of Poland caused a total outflow of the Jewish population from Książ. In September 1921 a synagogue was put up for sale. The building was bought by the city. In place of the demolished synagogue, a watchtower of the Volunteer Fire Brigade, created in 1928, was built.

The cemetery left after the Jewish community in Książ, located in the forest north of the city. Whether it was the same cemetery that served as the burial ground for the first Jewish settlers, we do not know. Confirmation of its location is found on maps from the 19th century. The cemetery survived until World War II. Most likely in the spring of 1940 it was devastated by the Nazi occupier. Broken matzevot served as building blocks. They laid curbs along today's Stacha Wichury Street and the pavement around the Evangelical church (today the church of St. Anthony). The matzevot were recovered in 2019. Work is underway to create a lapidary at the Jewish cemetery. They are the only trace of several centuries of Jewish presence in Książ.

Katarzyna Gwincińska

Bibliography:

Zygmunt Borys, Książ Wielkopolski. Zarys dziejów, Agencja Reklamowo-Promocyjna ROMAR, Jarocin, 1996

Alina Cała, Hanna Węgrzynek, Gabriela Zalewska, Historia i kultura Żydów polskich. Słownik, WSiP, Warszawa 2000

Dzieje Żydów w Polsce – zabór pruski, www.izrael.badacz.org, dostęp: 1.02.2020

Zenon Guldon, Jacek Wijaczka, Skupiska i gminy żydowskie w Polsce do końca XVI wieku, „Czasy Nowożytne”, Tom XXI, 2008

A. Heppner, J. Herzberg, Aus Vergangenheit und Gegenwart der Juden und der jued. Gemeinden in den Posener Landen, 1909, przekład własny: Magdalena Kaczmarek, WIR Książ Wielkopolski

Edward David Luft, The Jews of Posen Province in the Nineteenth Century. A Selective Source Book, Research Guide, and Suplement to "The Naturalized Jews of the Grand Duchy of Posen in 1834 and 1835", Washington, DC, 2015 Polski słownik judaistyczny, hasło: pogłówne, https://www.jhi.pl/psj/poglowne, dostęp: 1.02.2020

Das Bild der Synagoge in Książ basiert auf einer lithografischen Postkarte von 1904. Die Steinsynagoge wurde am 4. Oktober 1849 zusammen mit einer Grundschule eröffnet, deren Gebäude sich hinter der Synagoge befindet. Im Zusammenhang mit der Auflösung der jüdischen Gemeinde in Książ wurde die Synagoge im September 1921 versteigert. Das Gebäude wurde von der Stadt gekauft. Hier und aus diesem Baumaterial wurde ein Wachturm der Freiwilligen Feuerwehr errichtet.

In Książ [Xions] geborene Juden

Unter den in Książ geborenen Juden können wir heute kaum einige namentlich nennen. Unter ihnen - die beiden bekanntesten: Professor Heinrich Graetz und Dr. Samuel Kristeller, die in Enzyklopädien auf der ganzen Welt erwähnt werden.

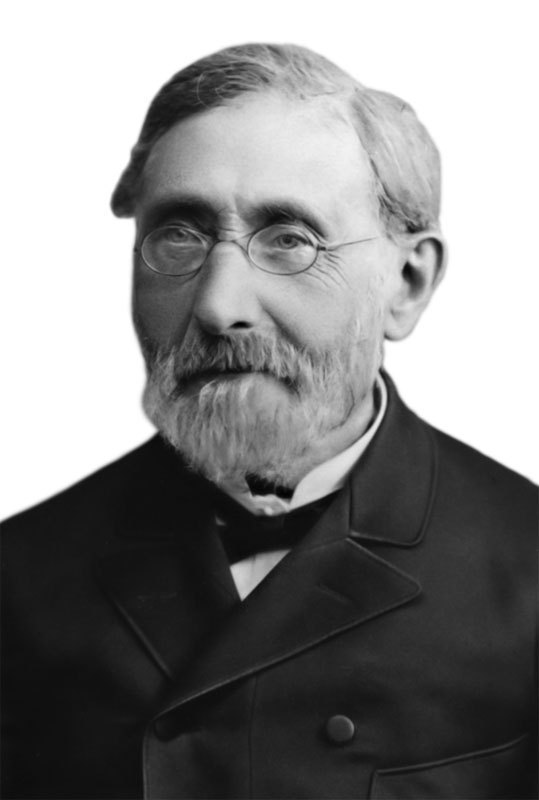

Heinrich Graetz (1817-1891)

Geboren am 31. Oktober 1817 in Xions [jetzt Książ Wielkopolski], Großherzogtum Posen; gestorben am 7. September 1891 in München war ein deutsch-jiddischer jüdischer Historiker. Seine Geschichte der Juden von den ältesten Zeiten bis auf die Gegenwart ist ein Standardwerk der Geschichtsschreibung des 19. Jahrhunderts und eine der wirkmächtigsten Gesamtdarstellungen der jüdischen Geschichte überhaupt.

Geboren am 31. Oktober 1817 in Xions [jetzt Książ Wielkopolski], Großherzogtum Posen; gestorben am 7. September 1891 in München war ein deutsch-jiddischer jüdischer Historiker. Seine Geschichte der Juden von den ältesten Zeiten bis auf die Gegenwart ist ein Standardwerk der Geschichtsschreibung des 19. Jahrhunderts und eine der wirkmächtigsten Gesamtdarstellungen der jüdischen Geschichte überhaupt.

Siehe: Wikipedia

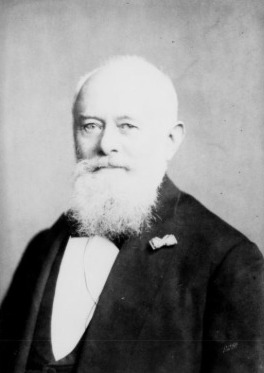

Samuel Kristeller (1820-1900)

Geboren 26. Mai 1820 in Xions [jetzt Książ Wielkopolski], Provinz Posen; gestorben 15. Juli 1900 in Berlin) war ein deutsch-jüdischer Gynäkologe.

Geboren 26. Mai 1820 in Xions [jetzt Książ Wielkopolski], Provinz Posen; gestorben 15. Juli 1900 in Berlin) war ein deutsch-jüdischer Gynäkologe.

Nach einem Medizinstudium an der Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität zu Berlin arbeitete Kristeller ab 1844 als Arzt in Gnesen. In den 1850er Jahren wechselte er zurück nach Berlin und wurde dort 1860 Privatdozent an der Universität, später Leiter der gynäkologischen Abteilung der Charité. 1867 wurde ihm der Titel des Sanitätsrats, 1873 der des Geheimen Sanitätsrats verliehen. 1868 trat er der Gesellschaft der Freunde bei. 1882?1896 wirkte er als Präsident des Deutsch-Israelitischen Gemeindebundes.

Siehe: Wikipedia

Berthold Baruch (1853-?)

Er wurde am 16. März 1853 in Książ [Xions] geboren. Er war Lehrer einer jüdischen Jungenschule in Berlin. Starb früh in Münster nach 1876.

Adolf Kwilecki (1863-?)

Er wurde am 30. Dezember 1863 in Książ [Xions] als Sohn eines Kaufmanns geboren. Er absolvierte das Gymnasium von St. Maria Magdalena in Posen im Frühjahr 1885 und praktizierte Landwirtschaft.

Meyer Feiwel Mendzigurski (1864-1943)

Er wurde am 2. April 1864 in Książ [Xions] geboren. Er war Religionslehrer und Kaufmann in Leipzig. Er wurde am 7. Dezember 1939 verhaftet und starb am 10. Februar 1943 in einem nationalsozialistischen Konzentrationslager (sogenanntes Durchgangslager) in Theresienstadt, Tschechische Republik.

Julius Thilo (1866-?)

Er wurde 1866 in Książ [Xions] geboren. Im Frühjahr 1885 absolvierte er Königliche Gymnasium in Śrem [Schrimm].

Regina Ullmann (1866-1942)

Sie wurde am 13. Juni 1866 in Książ [Xions] als Tochter von Sgaller geboren. Während des Zweiten Weltkriegs, von den Nazis aus Leipzig deportiert, starb sie am 12. Oktober 1942 im Ghetto Theresienstadt.

Hugo Kunz (1875-1943)

Er wurde am 23. Oktober 1875 in Książ [Xions] geboren. Er war Apotheker in Żory [Sohrau], später in Bytom [Beuthen]. Er starb 1943 nach der Deportation der Nazis.

Bruno Kunz (1881-?)

Er wurde am 2. Mai 1881 in Książ [Xions] als Sohn eines Kaufmanns geboren. Im Frühjahr 1900 absolvierte er die Fryderyk Wilhelm Gymnasium in Posen. Er wurde Doktor der Rechtswissenschaften und praktizierte zuerst in Posen, dann in Berlin. Er wanderte am 10. Februar 1940 aus Deutschland aus.

York (?) Kunz (1883-?)

Er wurde am 11. Mai 1883 in Książ [Xions] geboren. Sein Vater war später Mieter in Posen. Im Frühjahr 1903 absolvierte er das Friedrich-Wilhelm-Gymnasium in Posen. 1909 arbeitete er als Assistenzarzt in Gliwice [Gleiwitz].

Quellen:

1. Forschung der Wirtualna Izba Regionalna Gminy Książ Wielkopolski [Virtuelle Regionale Kammer der Gemeinde Książ Wielkopolski]

2. The Jews of Posen Province in the Nineteenth Century. A Selective Source Book, Research Guide, and Suplement to "The Naturalized Jews of the Grand Duchy of Posen in 1834 and 1835" by Edward David Luft, Washington, DC, 2015

(C)Stowarzyszenie Nasza Gmina, Charłub 2020-2025. All Rights Reserved